“The more we understand about this particular event in human history, the more it provides a complete picture of our past,” University of Washington evolutionary biologist Joshua Akey told New Scientist recently.

“This particular event in human history” is the early migration of humankind from the so-called Dark Continent to Mesopotamia, the Middle East and beyond, into Europe and, eventually, North America and the equatorial Pacific.

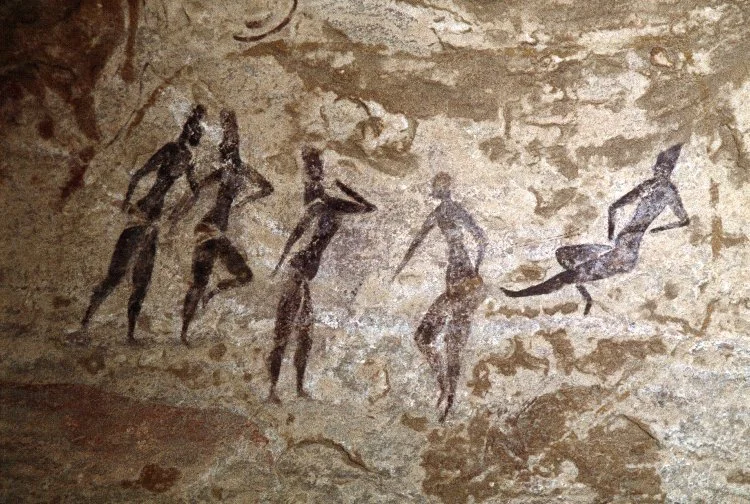

As much as is known about these early migrations — and we know a lot — much remains a mystery. This has been an active and unpredictable period for new discoveries about early humankind, from fossil evidence in regions as far-flung as the Rif mountains of Morocco to the Australian Outback. Incredibly, new cave art is still being discovered in areas of Europe that have been settled for millennia. Carbon dating continues to prove the old adage that the more we learn, the more we learn that we don’t know.

Modern humans emerged out of Africa — that much is reasonably certain — but exactly when, and how, remains the subject of fierce debate.

Two theories have jumped to the fore, emphasis on the word “theory.” One posits that our earliest ancestors left Africa in a single wave, around 40,000 to 60,000 years ago. Many of these groups died out, though, even as a handful passed their DNA to their descendants as they settled the break basket of the Tigris and Euphrates river valleys.

A new theory, which has gained traction of late, is that early humans migrated in several waves, not just one, and that the waves originated thousands of years earlier than was previously believed.

The answer, many scientists now believe, lies buried in our human genome. The authors of no fewer than three recent studies have analyzed the genomes of roughly 800 individuals from 250 populations scattered throughout the globe. In one study, Harvard geneticist David Reich argues that the clear genetic similarities between remote communities far removed from one another suggests that modern humans did indeed emerge in a single wave from Africa, even though DNA evidence shows that our earliest African ancestors were already dividing into separate groups more than 200,000 years ago — a full 120,000 years before that early migration, if the genetic findings are to be believed.

Early human development shows that rapid advances in technology, culture, art, language, religious rites and the use of tools occurred during a relatively short span of time, between 50,000 and 80,000 years ago — in other words, around the same time as those early migrations out of Africa.

In an early sign of how climate change affected human migrations, scientists now believe that fluctuating temperatures and an increasingly unpredictable life cycle of plant growth hastened the urge to move, even as the natural barrier ofmountains and deserts kept groups of people separate, leading to genetic differences in human populations around the world.

Separate genetics studies from Harvard, the University of Washington and the Estonian Biocentre in Tartu, Estonia suggest that while most modern non-Africans are indeed descended from a single, out-of-Africa exodus roughly 80,000 years ago, genome studies in Papua, New Guinea suggest there may have been an earlier exodus, according to Cambridge-educated molecular biologist Luca Pagani, senior researcher with the Estonian Biocentre in Tartu, Estonia.

Another recent study, this one supervised by evolutionary geneticist Eske Willerslev at Denmark’s University of Copenhagen, has found that indigenous groups in Australia are strikingly distinct, genetically speaking, from other groups in Australia, despite sharing the common gene that suggests they were all descended from a single, founding wave of early human migrations from Africa.

Why do we care? Why do we continue to care?

“People are just inherently interested in their past,” Akey told New Scientist, whether they’re from Seattle or South Yunderup township in Western Australia.

Answers inevitably lead to new questions, even as missing pieces in the puzzle are found. The mystery of early humankind — who we are, where we came from — continues to be one of the most fascinating riddles facing humankind today.