Everybody loves a good story. Even the best stories, though, can change in the telling.

Palaeontologists have argued for years — decades, in fact — that modern humans first emerged in Africa 200,000 years ago and migrated around the world some 50,000 to 100,000 years ago.

Exactly what route they took, though, where they left and where they arrived, is still the subject of much scientific conjecture and debate.

Now a recent study co-authored by the Department of Genetics at Harvard University Medical School in Cambridge, Mass. has brought scientists closer to understanding some of the finer details.

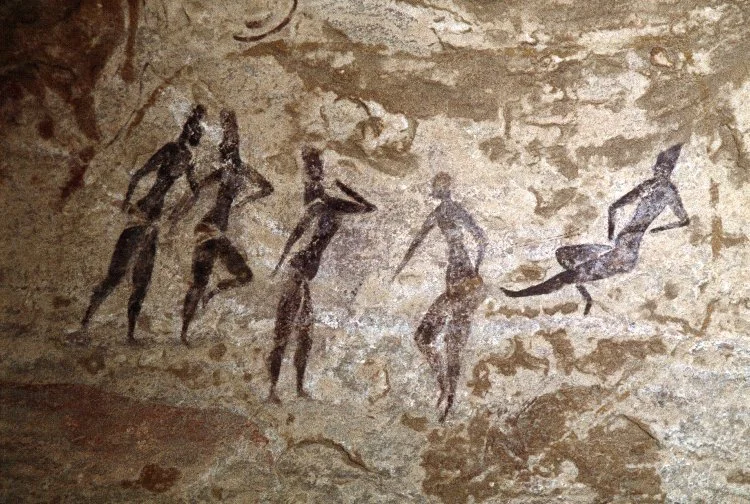

Humankind’s story begins in Africa with a group of hunter-gatherers, no more than a few hundred in all, who set out toward the distant horizon, for reasons known only to them. Today, 100, 000 years later, seven and a half billion of their descendants are spread throughout the Earth, “living in peace or at war,” as National Geographic geneticist Jamie Shreeve put it in a 2006 story for the magazine, “believing in a thousand different deities or none at all . . . faces aglow in the light of campfires and computer screens.”

The unanswered questions, shaped in the silence of prehistory, include: Who were these first modern humans in Africa? What compelled a small band of their descendants to leave the safety and security of the home they knew to set out for the unknown of Eurasia? Did they mix and intermarry other, earlier members of the human family tree along the way? When and how did early humans first reach the Americas?

The Harvard study, reported earlier this year in New Scientist, traced early human migrations by contrasting and comparing previously existing studies of ‘out of Africa’ routes with new DNA techniques that continue to improve the way scientists identify and sequence genomes of our early ancestors. The secret, the scientists say, is to find more efficient ways to analyze and understand the data, and improve our understanding of human migrations.

It’s a work in progress, the paper’s lead author, Dr. Mark Lipson, stressed. There are no easy answers. The secrets of those early human migrations remain just that.

Still, over time, more blanks on the giant, blank canvas of human prehistory are being filled in with each passing day. Incomplete maps are always subject to interpretation. “Here there be dragons,” inscribed on an old map, is always assumed to be true — or possible — until someone proves it isn’t. The slow, painstaking work of scientific discovery is often just as much about proving a negative as it is proving a positive. (Pedants, as typified by The Atlantic’s Robinson Meyer in a 2013 article, will point out that no old map, at least no early-modern European map, actually featured the inscription, Here there be dragons, but why spoil the beauty of a thing with an unprovable? All that means is that if there is a map with the words Here there be dragons or its Latin equivalent, Hic sunt dracones, inscribed on it, it hasn’t been found yet.)

Taking into consideration the possibility — likelihood, even — that early hominids interbred with other hominid species along the way, the Harvard study found that there was a definitive split between eastern and western populations once modern humans left Africa. This split happened as recently as 45,000 years ago, and explains how the early aboriginal inhabitants of Australia and New Guinea diverged genetically from their more northern cousins. Interestingly, unlike the closely studied migration of modern humans into Eurasia, the more southerly branch migration across Australia and the southern Pacific is less well understood.

What’s most relevant today about the study of early human migrations is whether any of these human movements were connected to climate change and, if so, how. Earlier research has suggested that humans spread across the globe in four waves, each one driven by climate change. The new findings suggest the picture may be more complicated than that, though. The Harvard study is a classic example of how, for every question answered, more doors open and more questions are asked.

Evolutionary scientists are naturally excited by the new findings, but Lipson urges caution. The process is slow and painstaking, as it should be. He urges against jumping to quick conclusions until more DNA evidence is found.

“There is some older archaeological evidence from Asia,” Lipson told New Scientist. “And while our results suggest the earliest human inhabitants probably would not have been closely related to Asian and Australian populations today, it would be interesting to see DNA from those sites.”

What we do know, based on DNA connected from 142 populations around the world, is that all non-Africans appear to be descended from a single group that split from the ancestors of African hunter-gatherers while, within Africa itself, humans formed isolated groups and then separated from each other.

The first migration did not end there. The study suggests that, subsequent to that first migration, there was a series of slow-paced migrations spread out over a period of thousands of years. Early Homo sapiens first arrived in southern Europe 80,000 years ago — far earlier than previously believed.

Question remain. Thanks to this new study and studies like it, the plot has thickened.