“Can a photograph change the world?” has become, “Can a photograph save the planet?”

More and more, nature and wildlife photographers prefer to label themselves as conservation photographers, in part to reflect the perilous state of the environment today, and in part because the word “conservation” suggests a bigger scale and broader reach.

“Conservation” sounds more important, somehow, though old-school nature photographers will argue that nature itself is the reason conservation matters. Nature, after all, provides the foundation on which conservation is built.

Voting has now closed for the People’s Choice Award in the 54th Annual Wildlife Photographer of the Year Awards, or WPOTY 54 in the photography community argot. Last year’s winners in all categories are on display at the Natural History Museum in London until May 28th; if past history holds, this year’s winners will be announced in October.

In a somewhat controversial decision — controversial to the outside world, that is, as the jury vote was unanimous, a first in the 50-year history of the WPOTY awards — the grand prize went to Getty Images photojournalist Brent Stirton for his gripping, tragic image of a slaughtered rhino.

Stirton’s background is hard news, not wildlife per se. After decades of covering conflict zones throughout his home continent of Africa — he cut his teeth photographing the anti-apartheid struggle in his native South Africa, before moving on to cover that country’s devastating HIV/AIDS crisis — he says he had an epiphany 10 years ago, in 2017, after photographing DRC (Democratic Republic of Congo) park rangers dragging a dead mountain gorilla out of the Virunga National Park rainforest, using makeshift ropes and heavy wooden beams.

Stirton had just enough time to take three frames before he had to leave, because, as he told The Guardian in Oct., 2015, “The army were looking for me.”

Stirton vowed then and there to become a lifelong crusader for the environment, using what he knows best to document the plight of endangered species, ecosystems and vanishing cultures throughout the developing world.

The People’s Choice award, by definition, is a vote by the people, and all that that implies.

It’s unlikely a picture of a dead rhino with its horn unceremoniously sawed off with a chainsaw would make the final cut for the People’s Choice Award, even if the finalists were chosen by a judging panel first and then submitted to the general public for a vote.

Even so, it’s hard not to look at the finalists’ images — a handful of which appear below — and not view them through the prism of what’s happening right now in the world’s few remaining wild places. It’s tough to see an image of a mother polar bear huddling over her newborn cubs and not realize that, within 20 years, polar bears may vanish entirely, owing to the catastrophic — and accelerating — ice melt in the northern polar regions.

Big cats often make for dramatic photographs, but again it’s hard to see a picture of a tiger today and not be reminded that it was the apex predators — the sabre-toothed cat, a remnant of the Pleistocene epoch for some 42 million years before dying out just 11,000 years ago, or the “super croc,” Sarcosuchus, an early ancestor of the crocodile, some 12 metres (39 feet) in length — that perished in the end, leaving their legacy to their smaller, more adaptable successors.

The difference now, of course, is that much of what’s happening is caused by human hands, and humans alone have the power to make a difference. Conservation photography is part of that.

This is not new. In 1864, Abraham Lincoln was famously so moved by Carleton Watkins’ stereographic illuminations of Yosemite, on the other side of the American continent, that he signed into law a bill declaring Yosemite Valley to be inviolable. Theodore Roosevelt enacted further protections in 1908, at the urging of his naturalist friend John Muir, founder of the Sierra Club. Yosemite played a key role in Woodrow Wilson establishing the U.S. National Park Service in 1916.

Today, photographers who document the beauty and wonder of the natural world have an added responsibility — wanted or not — to shine a new, white-hot light on the crisis facing the planet today, whether it’s something as simple and life-affirming as a sloth hanging out in the rainforests of Brazil, or as complex and hard-to-take as the bloodied hand of a poacher handling an elephant tusk in Central Africa.

Both have a story to tell. They are different, and yet tragically connected. It’s good that people know that.

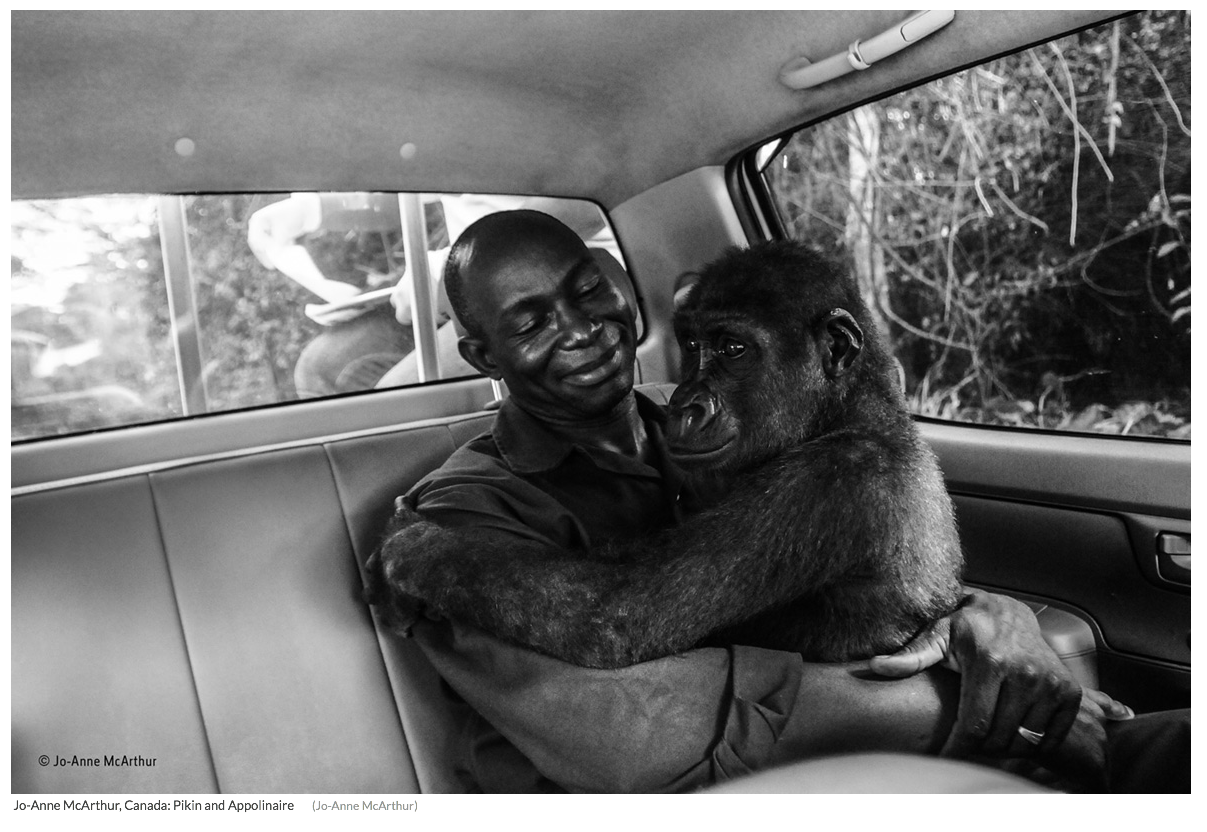

THIS JUST IN — Jo-Anne McArthur's "Pikin and Appolinaire" has been declared the People's Choice. Word broke late last night from the UK.

A strong image from a strong field, and well-deserving of the recognition. The conservation message is profound, no?