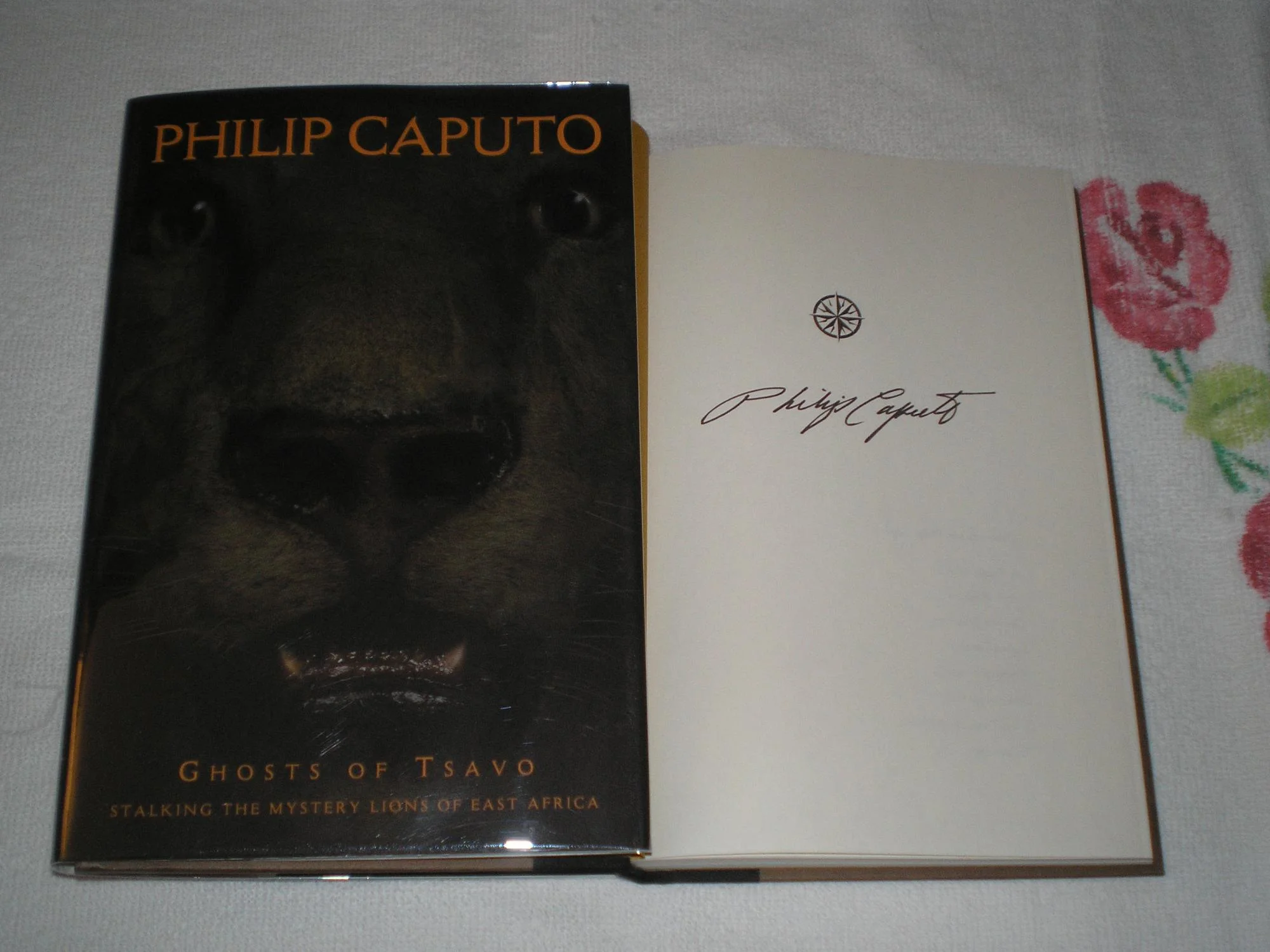

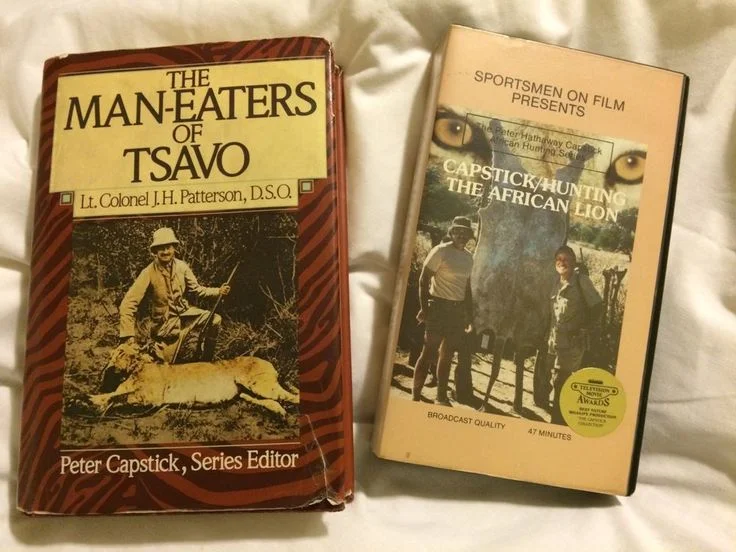

The notorious man-eating lions of Tsavo were the subject of two fine books, Lt.-Col. John Henry Patterson’s 1907 first-person account The Man-Eaters of Tsavo and Pulitzer Prize-winning writer Philip Caputo’s 2002 memoir Ghosts of Tsavo, and one perfectly awful Hollywood movie, director Stephen Hopkins’ 1996 clinker The Ghost and the Darkness. The film featured a game but ultimately unconvincing Val Kilmer as Col. Patterson, and an over-the-top Michael Douglas in the completely fictional role of “Great White Hunter” Charles Remington. Remington never existed; the events depicted in the film involving his character never happened.

The film was made in Zimbabwe, not Kenya; the lions in the film sported large, lavish Hollywood manes, unlike the maneless lions of historical record; and the lions themselves in the film came not from the wild but from a zoo in Bowmanville, Ont. They were named not “Ghost” and “Darkness” but rather Caesar and Bongo.

Despite Hollywood’s finest efforts to ruin a perfectly good story — Kilmer earned a 1997 Golden Razzie nomination for worst supporting actor — the actual story, in which a pair of man-eating lions killed and devoured 28 railroad workers (according to official records kept at the time) during the building of the Kenya-Uganda Railway in 1898, continues to have legs to this day.

Theories as to why the lions did what they did — debated openly and in absorbing, compulsively readable detail by Caputo in his book Ghosts of Tsavo— range from persistent drought and an outbreak of rinderpest at the time to Tsavo lying on the traditional slave-trade routes, which meant that lions in the area, being opportunistic hunters, were quick to dispose of any bodies that perished along the way.

A new theory, more scientifically detailed — and so less appealing to Hollywood moviemakers — has taken a different tack, and revealed some surprising results.

The fact that the Tsavo lions are still making the news in 2017 shows just how timeless the original history really is.

In a new study, Larisa DeSantis, a palaeo-ecologist at Nashville, Tenn.’s Vanderbilt University, used 3-D imaging technology to examine what remains of the Tsavo lions’ teeth, which have been preserved at Chicago’s Field Museum of Natural History. (How the lions’ remains, including a pair of life-size, mounted specimens for exhibit, ended up at the Field Museum is a story in itself, and another reason why Caputo’s book makes such absorbing reading.)

The first surprise is that, despite the lions’ fearsome rep for ferocity, the teeth are not sharp fangs and molars worn down by crushing and chewing on bone but rather the smooth, polished teeth one has come to expect of zoo lions, fed a steady diet a soft food such as days-old beef.

That suggests the railroad workers, far from being the lions’ preferred food, were simply part of a diverse, well-rounded diet that may have included whatever the lions could find.

Lions, after all, like all cats, are opportunistic hunters.

“We often see ourselves as the top of the food chain,” DeSantis told National Geographic’s online site earlier this week, “where in reality we have been on the menu of lions and large cats in general for a long time.”

As the late, legendary — and quite real — Great White Hunter Peter Hathaway Capstick wrote in his 1978 memoir Death in the Long Grass, all you are to an apex predator like a lion, or a crocodile for that matter, is protein. (In his later years, Capstickwrote that his hair didn’t turn grey so much as decline and fall out in clumps, owing to the sheer stress of being hired to track down man-eating leopards and lions in the miombo thorn-scrub of upcountry Zambia.)

DeSantis also points to dental disease — about as unromantic and unlikely a subject for a Hollywood movie as you’re likely to get — being a major factor in the Tsavo lions’ misbehaviour. One of the Tsavo lions had a broken canine and an abscess that would’ve affected the surrounding teeth.

Healthy, wild lions rely on their jaws to grab a large prey animal, such as a buffalo, around the neck and suffocate it, while trying to wrestle it to the ground, so persistent dental pain would be a constant, potentially life-threatening problem.

DeSantis’ co-author in the study, Dr. Bruce Patterson, renowned lion researcher and author of the definitive book The Lions of Tsavo: Exploring the Legacy of Africa's Notorious Man-Eaters, first published in 2004, has said that as many as 40 percent of Africa’s lions have some kind of dental injury, owing to the daily wear-and-tear of hunting in the wild. (Even a seemingly benign-looking animal as a zebra is tougher than it looks; any wild animal needs to be wily and physically strong to survive. A zebra can break a lion’s back with just one well-timed strike of its hoof; a healthy buffalo normally requires four or more lions to bring it down, and that’s on a good day.)

What’s interesting, of course, is how the 120-year-old tale of the Tsavo lions continues to raise new questions.

“One hundred years ago, the technology needed to answer this question wasn’t available,” DeSantis told National Geographic. “A hundred years from now, there will probably be new technologies we can apply.”

http://news.nationalgeographic.com/2017/04/man-eating-lions-teeth-kenya/?google_editors_picks=true