“Came for the comments war,” one commentator posted. “Wasn’t disappointed!”

“These (so-called) paleo-artists are nothing more than science-fiction artists,” another noted. “The most important skill they have is imagination, which has nothing to do with reality. As (the artist) says, ‘This is what they may have looked like.’ They keep trying to make monkeys out of us.”

“That’s why they call it ‘art,’” another countered. “It’s an interpretation. No one is trying to tell you what to believe. Too bad the same can’t be said about you!”

Whoa, there.

“Go to any museum,” the skeptic replied, “and see if they state that what you are looking at may be a bald-faced lie. I believe in science, but this whole field isbunk.”

Even if it is bunk, though — and there are plenty of experts who insist it isn’t — it’s compelling stuff.

What’s the point of being human if we’re not allowed to dream? Besides, recreating three-dimensional faces and even entire bodies from skeletal remains is a time-honoured, time-tested technique of forensic science, used in everything from cold-case murderinvestigations to ongoing missing-persons cases.

And there’s no question that leaders in the field — University of Kansas paleoartist John Gurche among them — are both respected in the scientific community and routinely have their work displayed at scientific institutions like the Field Museum in Chicago and the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History in Washington, DC.

Gurche is no dilettante. He frequently creates illustrations for National Geographic, created a set of four dinosaur-themed stamps for the US Post Service in the late 1980s and was one of the lead consultants on the original Steven Spielberg film Jurassic Park. More notably, perhaps, he published the 2013 book Shaping Humanity: How Science, Art and Imagination Help Us Understand Our Origins, in which he detailed his work on no fewer than 15 paleoanthropology displays he designed for the National Museum of Natural History’s Hall of Human Origins.

Gurche is currently Artist in Residence at Ithaca, NY’s Museum of the Earth.

He was most recently in the news for a Discovery Magazine article ‘Making Lucy: A Paleoartist Reconstructs Long-Lost Human Ancestors,’ which he both wrote and illustrated.

“I have an interesting job,” he deadpanned, then went on to explain how he created a lifelike, life-sized three-dimensional recreation of the most famous human ancestor ever unearthed.

“When I first learned of Lucy’s discovery, I wanted to make her (in her own image),” Gurche explained. “It is a wonderful endeavour to seek answers to questions about how she lived. Seeing her as she may have appeared in life can make a connection for us that nothing else can.”

‘Lucy’ is the name given to a 3.2-million-year-old partial skeleton found by Cleveland Museum of Natural History paleoanthropologist Donald Johanson on Nov. 24, 1974, near the village of Hadar, in Ethiopia’s Awash Valley. Lucy was believed to be the earliest known representative of Australopithecus afarensis.

Despite those who would dismiss Gurche and others’ work as so much junk science, paleoartists’ supporters in the scientific community note that paleoart is not the fantasy of an artist’s imagination but rather the result of cooperative discussions among scientists and artists alike. When trying to recreate an extinct animal — or person — the artist must employ both scientific knowledge and the mind’s eye.

Through exhibits at institutions like the Museum of Natural History and the Smithsonian’s Hall of Human Origins, paleoart shapes how the public perceives long extinct animals and early humans.

The Society of Vertebrate Paleontology has awarded the John J. Lanzendorf Prize in Paleoart since 1999. Gurche won the award in its second year, in 2000.

The society describes paleoart as “one of the most important vehicles for communicating discoveries and data among paleontologists, and is critical to promulgating vertebrate paleontology across disciplines and to lay audiences.”

That’s a dry way of saying paleoart is not only cool to look at; it also serves a useful scientific purpose.

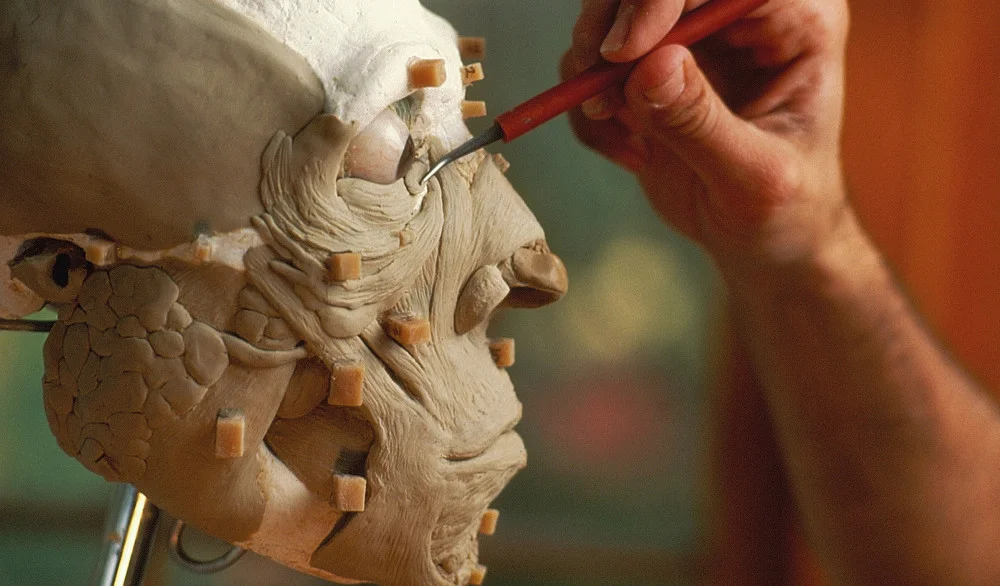

In Gurche’s paper, he outlined how, in 1996, the Denver Museum of Nature and Science commissioned him to produce “a life-sized, three-dimensional reconstruction” of Lucy, as lifelike as methods at the time would allow.

Gurche explained how first he had to settle on a pose.

“Was there a way to represent both climbing and upright walking in the same pose?” he wrote. “It would be tricky, but perhaps I could depict a moment of transition, where it’s obvious that Lucy is climbing down from a tree, and equally obvious that she’s dropping into an upright position, as opposed to dropping to all fours.”

Gurche went on to explain how he constructed a 3-D version of Lucy’s feet — “one foot in front of the other” — then based his reconstruction of Lucy’s face on a composite female skull, with more dainty features than a male.

“Lucy’s skeleton displays many clues about the position and development of her musculature,” Gurche noted. “These can be ‘read’ using the anatomy of modern apes and humans as guides.”

There’s room for creative licence, in other words.“Bunk,” thnough, is a harsh word, especially when one realizes the lengths to which Gurche went to ensure at least a modicum of scientific accuracy.

“The amount of body hair in australopiths is unknown,” Gurche explained. “We assume that the common ancestor of chimps and humans, like all the non-human apes, had a full coat. We can guess that this coat was lost by the time of Homo erectus, as (the) skeleton’s proportions show that it was adapting to heat stress, much as modern humans do. Part of our adaptation involves an enhanced sweat gland cooling system, which would not function well with a full coat of body hair.”

Got that? Good.

“About a million individual hairs were punched into Lucy’s silicone skin over a period of three months in each of her incarnations,” Gurche added, “for the Denver museum and later for the Smithsonian *as well).”

That’s a lot of work to go through if the end result is, as paleoart’s detractors insist, little more than junk science.

And the effect is truly remarkable. It’s difficult — impossible, even — to look at Gurche’s work and not feel at least a pang of human curiosity and recognition.

The Smithsonian, National Geographic and the Natural History Museum can’t all be wrong.

http://discovermagazine.com/galleries/2013/dec/paleoartist-reconstructs-human-ancestors