“Those who deny scientific findings in favour of magical thinking and other fallacies will only leave the world a more unstable and dangerous place for future generations.”

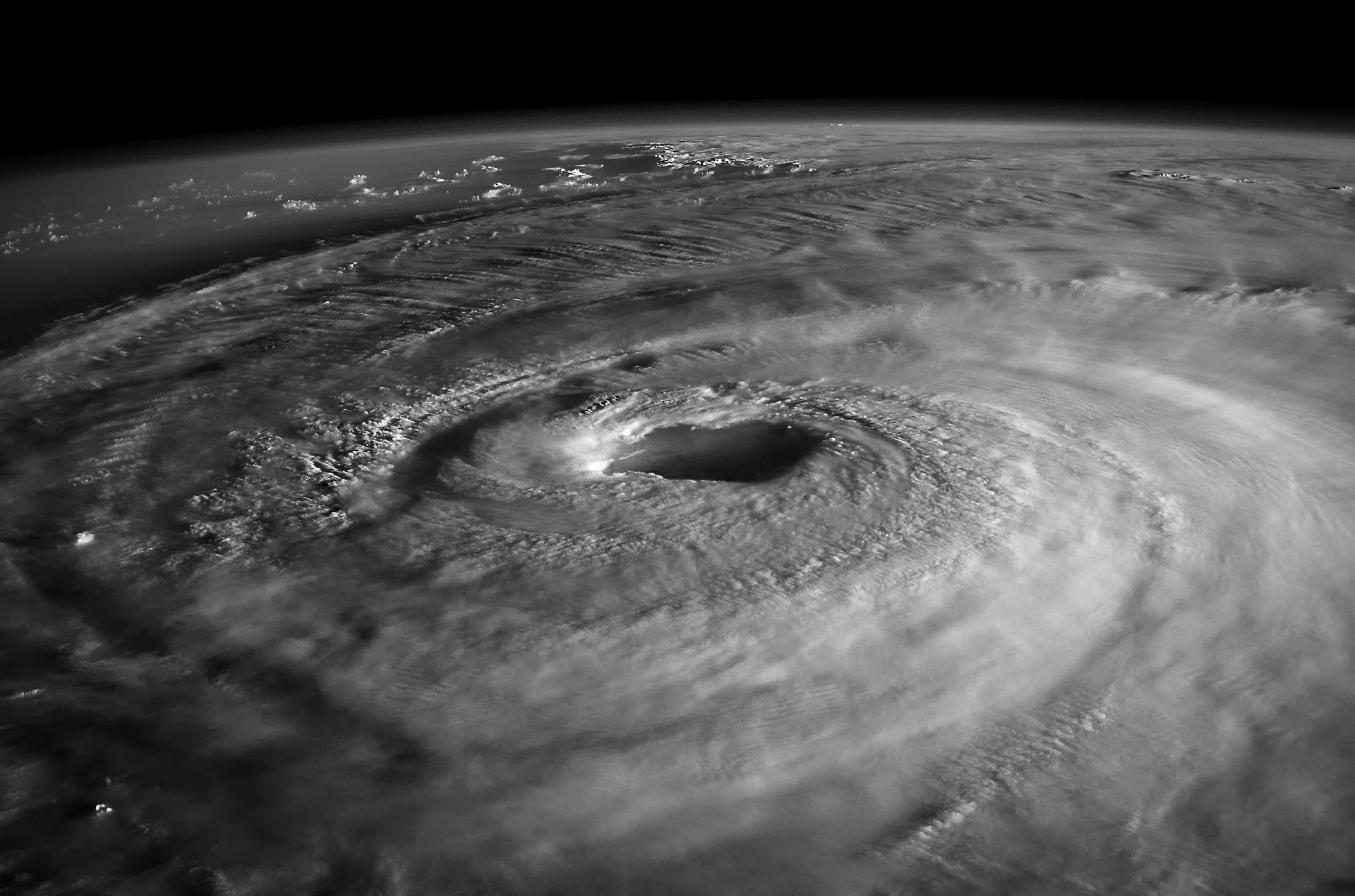

It has been a punishing several years for people who live in the path of hurricanes in the Atlantic. Hurricanes are low pressure weather systems that feed off warm water and atmospheric moisture. They always gather pace, unless slowed by dry air, crosswinds or landfall.

At their most basic, hurricanes are tall towers of wind which can grow as high as 60,000 feet (18,000 metres) in some cases — nearly twice the cruising altitude of most commercial airliners. Storms are given names once they reach sustained winds of 40 mph (65 kph) or more, and are measured on something called the Saffir-Simpson scale, which rates wind speed on a scale from one to five.

A storm is classified as a major hurricane once it reaches category three, which means wind speeds of 110 mph (180 kph) or more — enough force to damage homes and snap trees in half. A category five storm is one that reaches wind speeds of 160mph (260 kph), powerful enough to flatten communities, cause widespread power outages and result in numerous deaths.

Strong recent hurricanes include Katrina (New Orleans, 2005), Harvey (Houston, 2017) and Maria (Puerto Rico, 2017).

Hurricanes are in the public eye today because June 1 marks the official beginning of hurricane season, which runs until Nov. 30.

Today’s date is key because many climatologists believe global overheating will inevitably lead to bigger, more deadly hurricanes. An overheating planet means warmer oceans, which results in stronger winds, which in turn leads to more violent, intractable storms. More moisture in the air means more rain, which means more flooding in the storm’s aftermath.

Here’s why the experts are worried. The 2017 hurricane season unleashed devastation on a scale rarely seen before. Hurricanes that year caused a record USD $282 billion in damage; Hurricane Harvey alone unloaded 33 tn gallons of water on Texas. Winds unleashed by Hurricane Irma reached top speeds of 180 mph (285 kph) ravaged Florida, and residents of Puerto Rico are still counting the cost — in lives and property — of Hurricane Maria.

The overall number of hurricanes has remained roughly the same over the past several decades. The difference is that they’re intensifying more quickly, which has resulted in a marked increase in the number of stronger category four and five storms, and fewer category three storms. When hurricane force increases over a narrower time frame — 24 hours in some cases — it makes hurricanes harder to predict, and more likely to cause damage and loss of life.

The science is still out on whether the climate emergency is to blame, but it’s clearly not helping. There’s growing evidence that the combined warming of the atmosphere and ocean surfaces makes conditions for more intense, destructive hurricanes more likely. Much of that warming is due to human activity, through carbon emissions and our growing use of fossil fuels.

The real cause for concern, of course, is that there are more people in harm’s way today. In the southeastern continental US, coastal populations have increased by roughly half — 50% — since 1980. It hasn’t helped that environmental protection laws and emissions standards, passed by earlier presidential administrations, have been scrapped by You Know Who.